Una campagna di Alessandro Nesi

ContattiRecupera la tua password

Inserisci il tuo indirizzo email: ti invieremo una nuova password, che potrai cambiare dopo il primo accesso.

Password inviata

Controlla la tua casella email: ti abbiamo inviato un messaggio con la tua nuova password.

Potrai modificarla una volta effettuato il login.

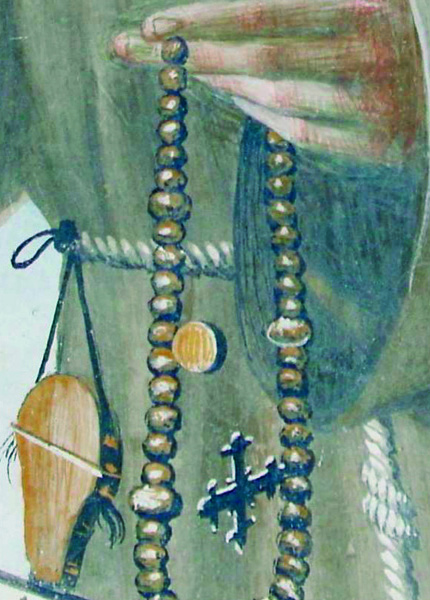

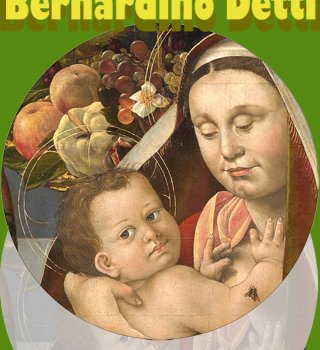

progetto per una monografia su Bernardino Detti, pittore stravagante e misterioso del Cinquecento

- Raccolti € 0,00

- Sostenitori 0

- Scadenza Terminato

- Modalità Raccogli tutto Informazioni

Raccogli tutto

Il tuo contributo servirà a sostenere un progetto ambizioso. Scegli la ricompensa o la somma con cui vuoi sostenerlo e seleziona il metodo di pagamento che preferisci tra quelli disponibili. Ti ricordiamo che il progettista è il responsabile della campagna e dell'adempimento delle promesse fatte ai sostenitori; sarà sua premura informarti circa come verranno gestiti i fondi raccolti, anche se l'obiettivo non sarà stato completamente raggiunto. Le ricompense promesse sono comunque garantite dall’autore.

- Categoria Libri & editoria

Commenti (1)